Days of Darkness

Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht evolved as a conservative German who agreed to serve in Hitler’s government from 1933 into 1939 as president of the Reichsbank. He wore a “second hat” as Minister of Economics from 1934 into 1937.

As president of the Reichsbank in his first stint (1923 to 1930) he was provided with a city apartment convenient to his office; in his memoirs he recollected that it offered little privacy. This was balanced by a rural retreat:

“In 1926 I acquired a property about seventy miles north of Berlin, not far from Rheinsberg and Neuruppin. Gühlen, with its well-wooded grounds, surrounded by lakes, became in truth a source of recreation for me.” —- “On leaving the Reichsbank my wife and I finally moved out to Gühlen, the property I had acquired in 1926.”

Schacht, My First Seventy-Six Years

By the middle of 1933 he was intensely engaged in his return to the Reichsbank. In his memoirs he has a reference to being in the bank’s city apartment in 1937.

In 1935, Walther Funk moved into the villa at Sven-Hedin-Strasse 11. If Hjalmar Schacht used the villa, it is likely that he was using it between mid-1933 and 1935 as a place for bank meetings or official gatherings. He had no need for another home.

It is not the intention of this article to trace the entire career of one of the many supporting actors in the National Socialist drama. However, Walther Funk’s rise in status was reflected in his Berlin homes. And, it may be connected to the belief that Hjalmar Schacht lived in the villa.

This is another good place for a side trip. Readers who have a basic knowledge of German will be interested to note that a popular history of Sven-Hedin-Strasse 11 omits Funk entirely.

Funk was a complex character. He drew the interest of the CBS Berlin correspondent, who noted in his diary:

“From Dr. Walther Funk, president of the Reichsbank and Minister of Economics, we also received a first glimpse into Hitler’s “new order.” Funk, a shifty-looking little man who, they say, drinks too much, but who is not unintelligent and not devoid of humour, admitted quite frankly that the purpose of the “new order” was to make Germany a richer land.”

William L. Shirer, Berlin Diary, on 25 July 1940.

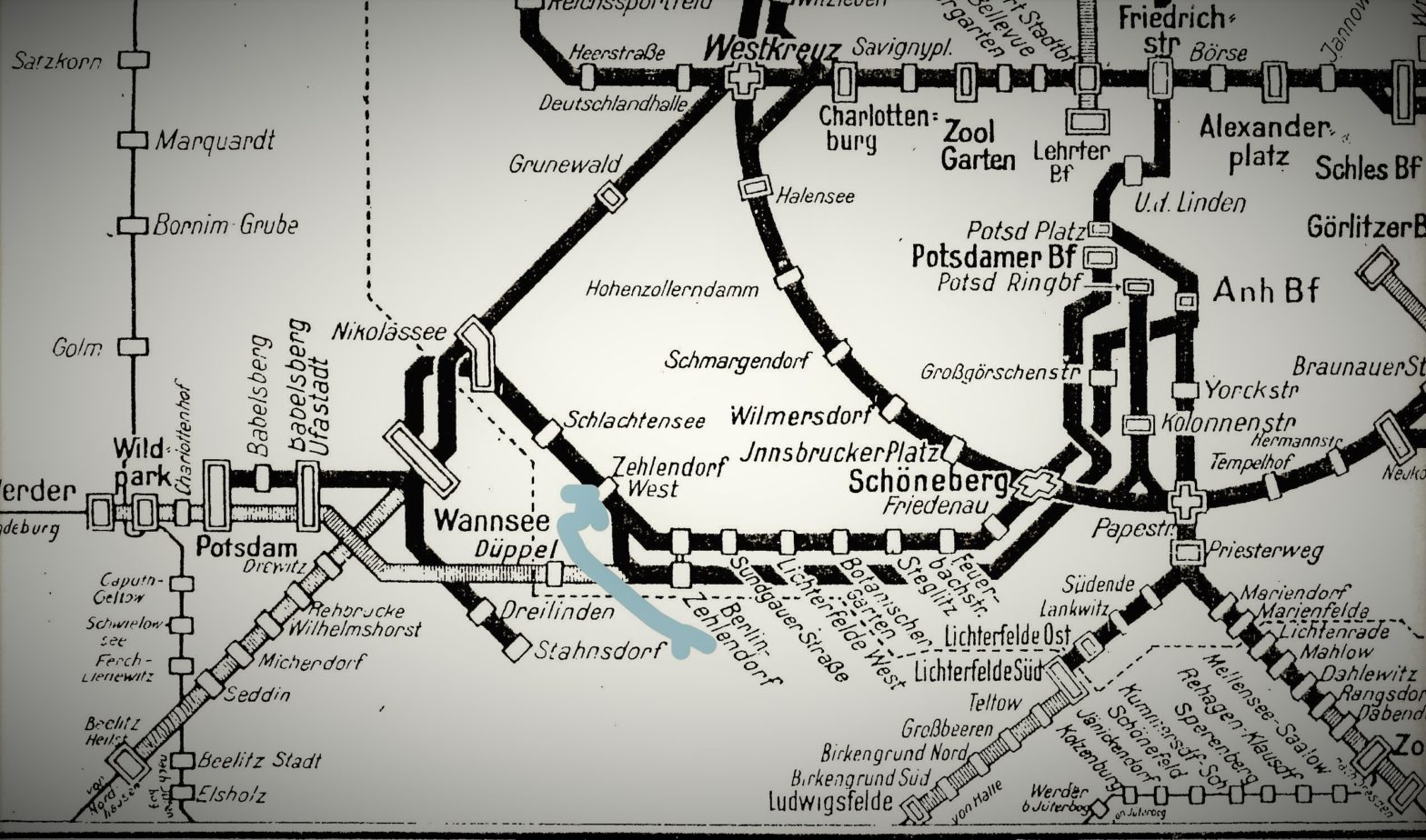

Funk began his Berlin residence coming from a career as a former business and economics journalist turned Nazi propagandist. He was able to communicate with types of people who were uncomfortable with others in the ruling circle. In 1932-34 he lived in the “villa colony” of Schlachtensee at Dübrowstrasse 29, listing his work as “editor-in-chief” in the city directory. He supervised the Reich Press Bureau, basically a public relations agency for the government.

The 1935 International Who’s Who published in London gives his address as being at the central Berlin office of the Propaganda Ministry on the Wilhelmplatz. Published later that year, Wer ist’s and the city directory showed him living at Sven-Hedin-Strasse 11. Wer ist’s also noted that his family had been Evangelisch (Lutheran) since the 1600’s and that he had sailed to New York in 1927.

Funk – as mentioned above – moved in circles where he came to the attention of society page journalists:

” Musical entertainment in the home of the French diplomat Pierre Arnal and his wife. Very posh. I am interested especially in Walther Funk and his wife. The stout Walther has never been very popular. Usually he is not quite sober. I still remember the time when he was very friendly with the non-Aryan Emil Faktor [editor] from Börsen-Courier. The two were inseparable. He is now Secretary of State in RMVP [Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda (German: Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda, or Propagandaministerium)]; his position requires that he lives in a magnificent palace. God knows who Funk has chased from his home to get this current home in the Sven Hedin road … “

Bella Fromm, her Berlin Diary, on 14 January 1936

Wikipedia biographies show that both Walther Funk and Emil Faktor left the Berliner Börsen-Courier in 1931. Faktor, a secular Jew who was asked to leave, returned to his Prague hometown to scrape out a living as a free-lancer; his life ended in 1942 in the Łódź Ghetto. Walther Funk went into politics.

By 1938 the International Who’s Who showed that Funk had been busy: after his post as chief of the Reich Press Bureau and his appointment as Secretary of State in the Ministry of the National Economy and then in the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, he had served as vice-president of the Reich Cultural Chamber, as chair of the Publicity Council of German Industry, as chair of the Reich Broadcasting Association, and as chair of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (Vorsitzer des Verwaltungsrat).

In these positions he would have been responsible for guiding the organizations along National Socialist party lines. Nazi leadership did not have total control over society. For example, Eugen Jochum continued to conduct the Hamburg symphony in works by banned composers.

Funk’s propaganda assignment led him down many odd paths. Strangest perhaps was his role in currying favor with the world-renowned explorer Sven Hedin. The Swede — for whom Sven-Hedin-Strasse coincidentally had been named — was sympathetic to Germany and the RMVP aided him in researching of a book on the Reich. Problems developed when Hedin insisted on being critical of some aspects of National Socialism. The explorer had his work published in an uncensored version in Sweden in September, 1937. A German translation was ready, but Funk wanted to delete the dangerous passages. Deadlocked, it was not published in German until a complete translation in 2014.

Funk’s place in the pre-war Nazi hierarchy is reflected in a page from the 25 April 1937 weekend pictorial magazine of Berliner Tageblatt. He was on hand to celebrate his Führer’s 48th birthday along with his boss, propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels.

In the meantime, Hjalmar Schacht was becoming more and more of a problem for the new order. Preparations for war contradicted his economic development plans. He had tendencies toward outspokenness; he attended services at Zehlendorf pastor Martin Niemoller’s church where sermons challenged government control of religion.

In November 1937, Schacht was removed from his cabinet portfolio of Reich Minister of Economics, staying on as Reichsbank president into 1939. Reliable Walther Funk succeeded him in both posts. As a business journalist he had an understanding of economics and finance, but did not have the world wide reputation held by Schacht. I have found no evidence — in spite of the neighborhood legend — that Schacht ever lived in the Sven-Hedin-Strasse.

Foreign journalists noted improvements in the Propaganda Ministry’s operations after Funk was replaced there by Dr. Otto Dietrich, a longtime friend of Hitler.

“The conference held in this fashion [last of the day, for foreign press and radio] since 1933 had not been fruitful. Information was given, but it was largely routine, and many questions were met by the reply, “hier ist nicht bekannt” — the equivalent of “there is no information on that” or of “no comment” — and correspondents tended to ignore the conferences.

“Matters improved, however, after Dr. Dietrich became undersecretary and chief of the Press Department in the Propaganda Ministry in January 1938.”

Robert W. Desmond, Tides of War

Walther Funk needed an even more elaborate residence in his new position: Am Sandwerder 17-19 had been the home of Hans Arnhold, prominent banker and cultural leader. The Arnhold family, Jewish, had turned their villa over to the Reichsbank in a forced sale after their timely move out of Nazi Germany. In 1938, newly minted Reichsbank president Walther Funk moved out of the “magnificent palace” on Sven-Hedin-Strasse and into the lakeside villa on Am Sandwerder. He moved out of this website’s history toward the dock in a Nuremberg courtroom.

https://www.americanacademy.de/about/hans-arnhold-center-history/

In the dark current of events leading into World War II it is often the case that readers organize their thoughts from the point of view of their country’s role. This is especially understandable when so many pieces were moving on the global chess board at the same time.

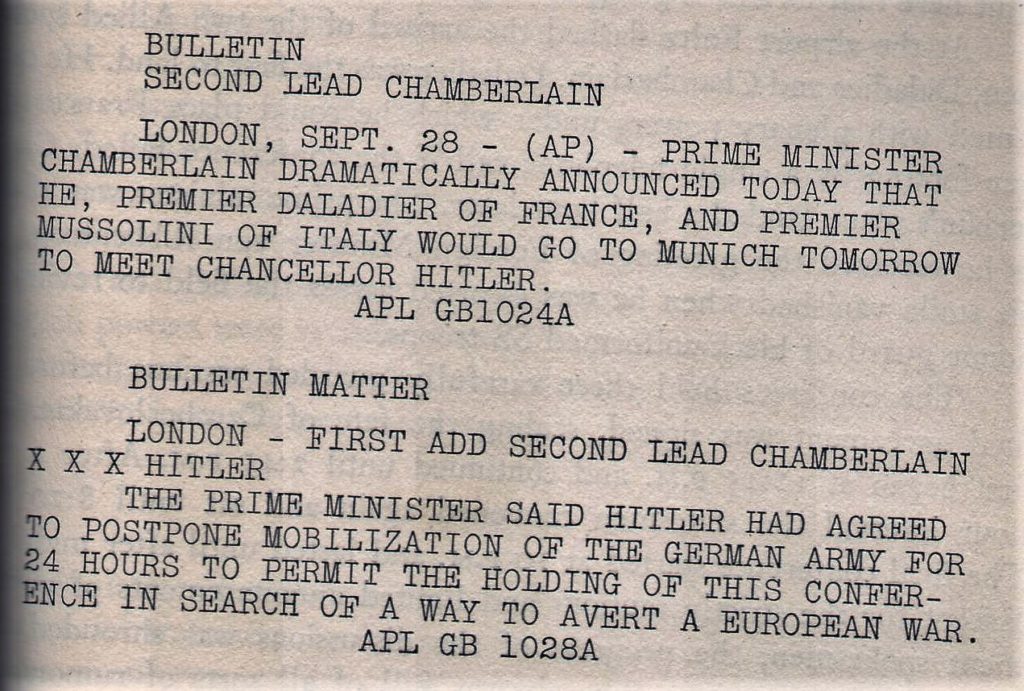

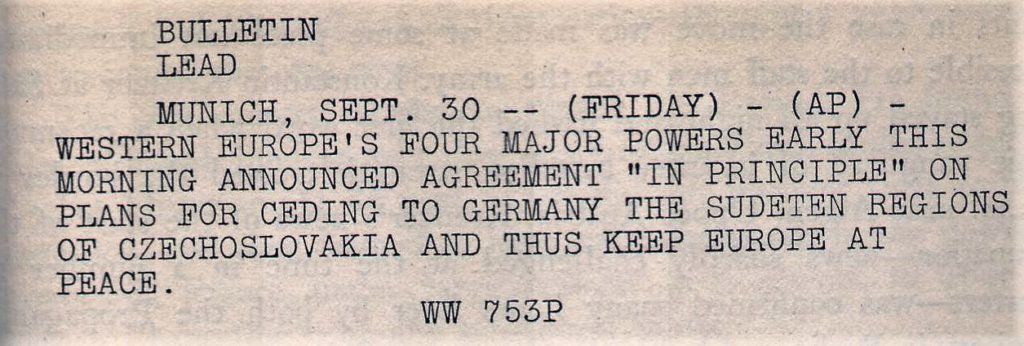

Anglophone readers know about “peace in our time” in 1938, but what happened to Czechoslovakia after that?

The trail leads from Munich on 30 September 1938 to Sven-Hedin-Strasse 11 to privately expressed anguish to an honored cremation in the chaotic last days of the Third Reich. And finally posthumous honors for service to Germany.

It is not clear when František Chvalkovský moved into the villa. In early October 1938 he was appointed Foreign Minister, moving from Rome, where he had served as ambassador, to Prague, the capital city of Czechoslovakia. This was on the heels of the “peace in our time” deal. He had been posted as ambassador to Germany in 1926 and according to the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung had good relations with governments in the Berlin-Rome axis. This Nazi-censored paper reported that he also worked well with other small Central European countries.

By October 12th he was in Berlin meeting with Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop. He was back in Prague in November as Czech and Slovak politicians struggled to reorganize their government after the Munich agreement shock. Some there touted him as a possible president. Instead, the remaining Czechoslovak leaders selected the elderly Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Emil Hácha.

Talks with Berlin continued as anxiety and cynicism in Czechoslovakia grew. In January 1939 the German chargé de affaires in Prague reported that:

“Considerable enmity has been shown toward Foreign Minister Chvalkovský, and special provisions have to be made for his personal safety.”

from the archives of the German Foreign Ministry

Within the Republic, Sudeten Germans continued to agitate, even setting up a secret telephone link with Berlin. To the east, Slovakian politicians, aided by the German Reich, talked secession.

On 14 March 1939, Slovaks declared independence. A special train raced from Prague to Berlin that evening. Departing the Czech capital at 4:00 p.m., it arrived in the Reich capital at 10:40 p.m., half an hour faster than a typical express. The special carried the acting Czech President Hácha; in his company were František Chvalkovský, other Czech diplomatic staff, and Hácha’s daughter.

On the platform in Anhalter Bahnhof to greet them were officials of the Czech embassy, the freshly commissioned Slovakian ambassador and a German delegation headed by Chief of the Presidential Chancellery of the Führer and the Chancellor, Dr. Otto Meissner. Meissner was a holdover from pre-National Socialist days and his main function seemed to be ceremonial.

In the newsreel clip below František Chvalkovský is on the left side of the photo.

When word of the desperate mission became public a crowd gathered at Anhalter Bahnhof. The Hamburger Fremdenblatt reported that railway police (the bahnpolizei) set up barricades to control the onlookers, photographers and newsreel cameramen.

The crowd observed the arrival of the Czech dignitaries in silence. The platform for convenient Track 9 had been closed to the public, but a work area had been set up for the cameramen and the press — especially, commented the Hamburg paper — the foreign, “Anglo-Saxon” press. The Czech interim president alighted from the green official car of the short special train first, followed by the foreign minister. When the president’s daughter stepped down from the car she was presented with flowers.

Dr. Meissner led the party through the adjacent royal waiting room and out to the plaza in front of the 1841-vintage building. Everything was in order.

Outside of the station a Wehrmacht honor company was formed up on the plaza under the flag of the Watch Regiment of Berlin. To the sounds of the order to “present arms” and the Presentation March, President Hácha was given routine military courtesy. Then the party was reportedly taken to the Hotel Adlon.

If that was correct, Hácha and Chvalkovský were not long at the grand hotel. The French ambassador reported to his government:

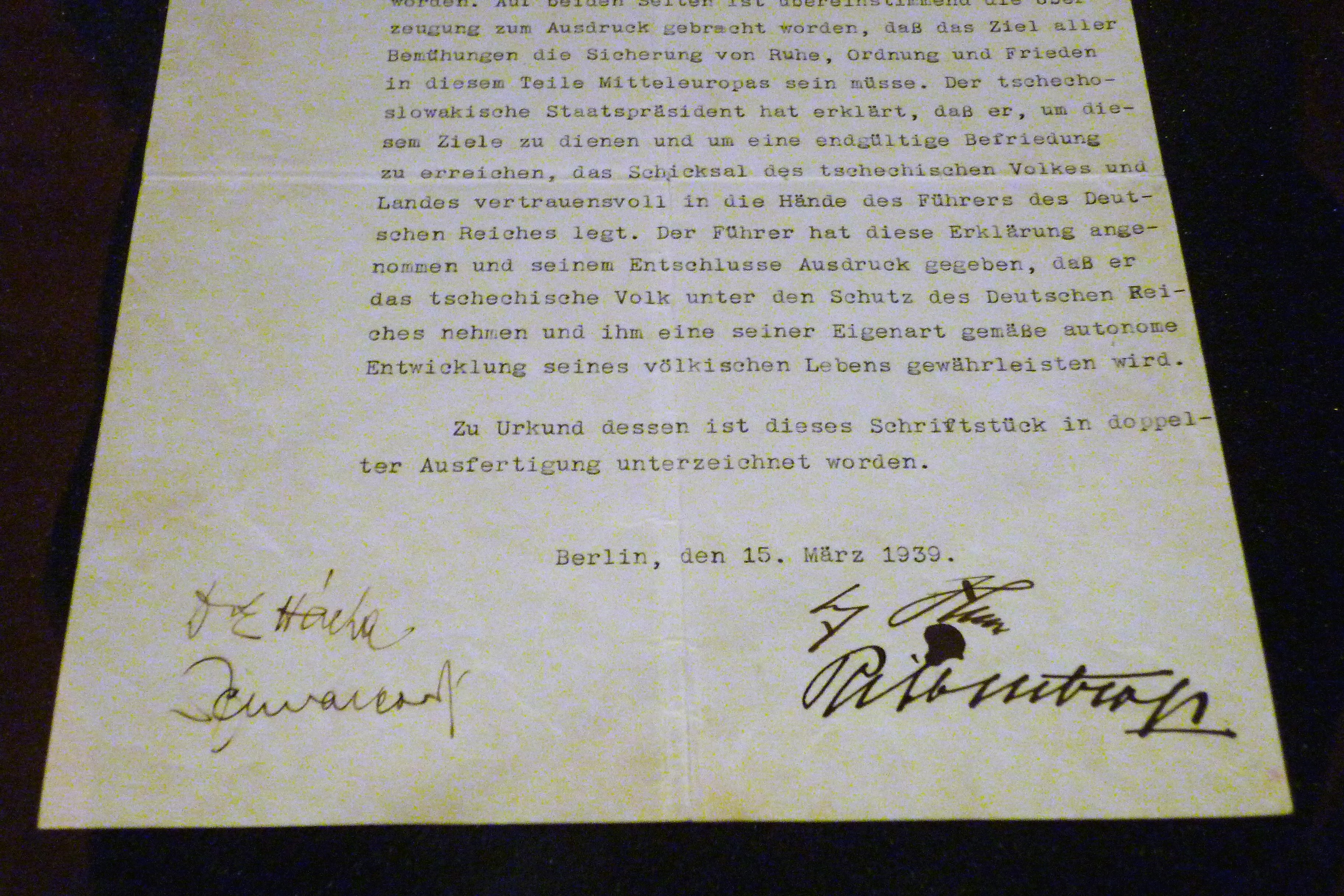

Immediately on arrival, M. Hácha and his Minister, who were received with military honors, were taken to the Chancellery where Herr Hitler, Field-Marshal Goering, Herr von Ribbentrop and Herr Keppler were waiting for them.

The document to be signed lay waiting on the table, in its final form, as well as a memorandum relating to the future Statute for the administration of Bohemia and Moravia.

The Fuehrer stated very briefly that the time was not one for negotiation but that the Czech Ministers had been summoned to be informed of Germany’s decisions, that these decisions were irrevocable, that Prague would be occupied on the following day at 9 o’clock, Bohemia and Moravia incorporated within the Reich and constituted a Protectorate, and whoever tried to resist would be “trodden underfoot” (zertreten). With that, the Fuehrer wrote his signature and went out. It was about 12:30 a.m.

An intense session occurred as the Germans pressed for signatures on the document they already had prepared. Conflicting accounts are from French and German officials. The French report (here translated into English on line) was based on confidential sources.

https://avalon.law.yale.edu/wwii/ylbk077.asp

The American diplomatic report is also on line, along with reports of the rapid Third Reich takeover of the Czech Republic.

https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1939v01/ch2

The British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Viscount Halifax, addressed the House of Lords:

“The German military occupation of Bohemia and Moravia began on the morning of the 15th March, and was completed, as we know, without serious incident. It is to be observed — and the fact is surely not without significance — that the towns of Mährisch-Ostrau and Vitkovice were actually occupied by German S.S. detachments on the evening of the 14th March, while the President and the Foreign Minister of Czecho-Slovakia were still on their way to Berlin and before any discussion had taken place.”

Speech on 20 March 1939 quoted in the British War Blue Book.

On March 16th the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was proclaimed as successor to the Czech Republic and Chvalkovský was named as its representative in Berlin — with the title of Ambassador. In his new situation he was provided with a house — Sven-Hedin-Strasse 11 — that was not a home, but after all, as the Protectorate officials recognized, he was not really an ambassador.

Nevertheless, he openly carried out work that might be considered consular affairs. One of the first issues was the status of Czech students who had been in German universities on March 15th and were held in “protective custody.” From the Czech point of view they were hostages.

Privately, he carried out activities that represented long-term Czech interests. The elaborate doors of Zehlendorf villas opened to the homes of leading military and government officials, but also to planners of the resistance. In August 1940 he dined with three men who in 1944 were executed for their part in anti-Hitler plots. Joining them at the dinner was another man who always seemed to show up at critical times — Hjalmar Schacht.

Meanwhile in Prague, the Sudeten Germans who were now running day to day affairs were searching Chvalovský-related files at the former Czech/Czechoslovakia foreign ministry. Apparently they found nothing that would be retroactively incriminating.

In March 1941 the ambassador returned to Prague for a few days and his meetings with Czech political figures were monitored. Travel for official purposes was still relatively easy. Relations between the Czech-run civil government which included Chvalovský and the occupation Protectorate run by the SS (State Security Service) were not good. Memos among the Protectorate leaders discussed the problems with what they termed as a “two-track” situation:

+ Reichs Protector <==> Autonomous Czech Government

+ Envoy Chvalkovský <==> Reich Ministries in Berlin.

Further friction was revealed by complaints that Chvalkovský communicated with the Czech government officials in Czech. When the Protectorate officials complained, he pointed out that the former Austro-Hungarian government had permitted their use of Czech as a convenience.

Secret!

According to a report here, Chvalkovský viewed the current situation in the Reich as critical and stated that the crisis would come with mathematical certainty. This attitude was also expressed in the following incident: On the occasion of his last vacation in Prague, Chvalkovský suddenly stopped playing the piano with his sister and commented that “If things go wrong, we both could play in a bar.”

A secret memo to K. H. Frank from the SS in Prague dated 11 August 1943.

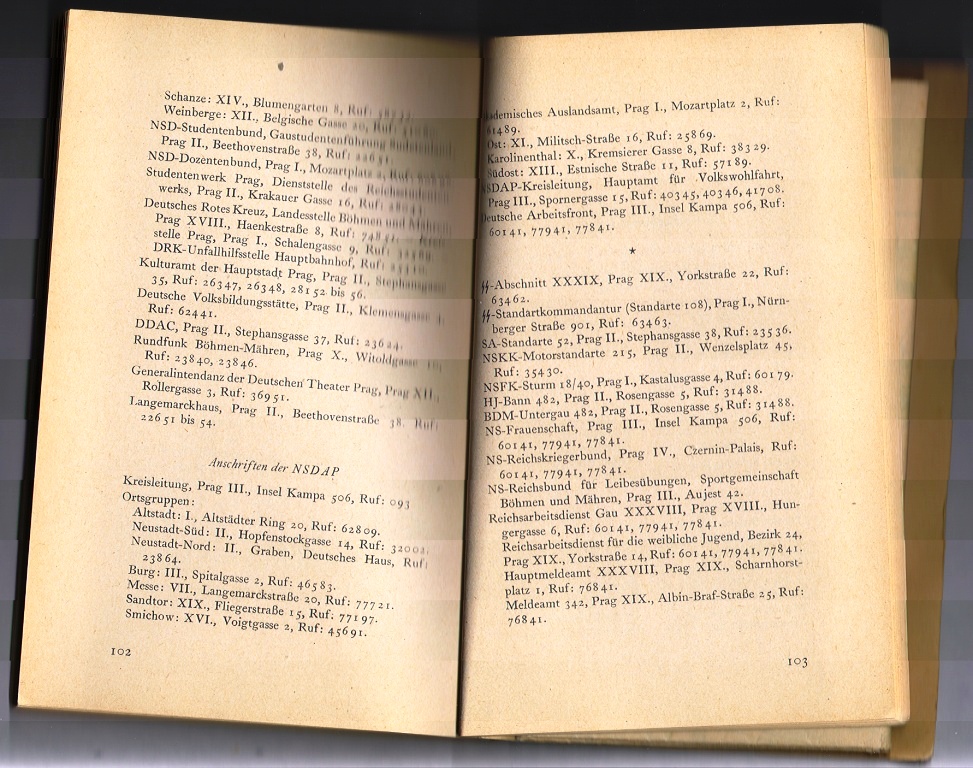

The SS and the Nazi party were busy in the Protectorate. A pre-war tourist guide in German was re-edited for the new situation. These two pages offer an idea of how overwhelming the political side attempted to be.

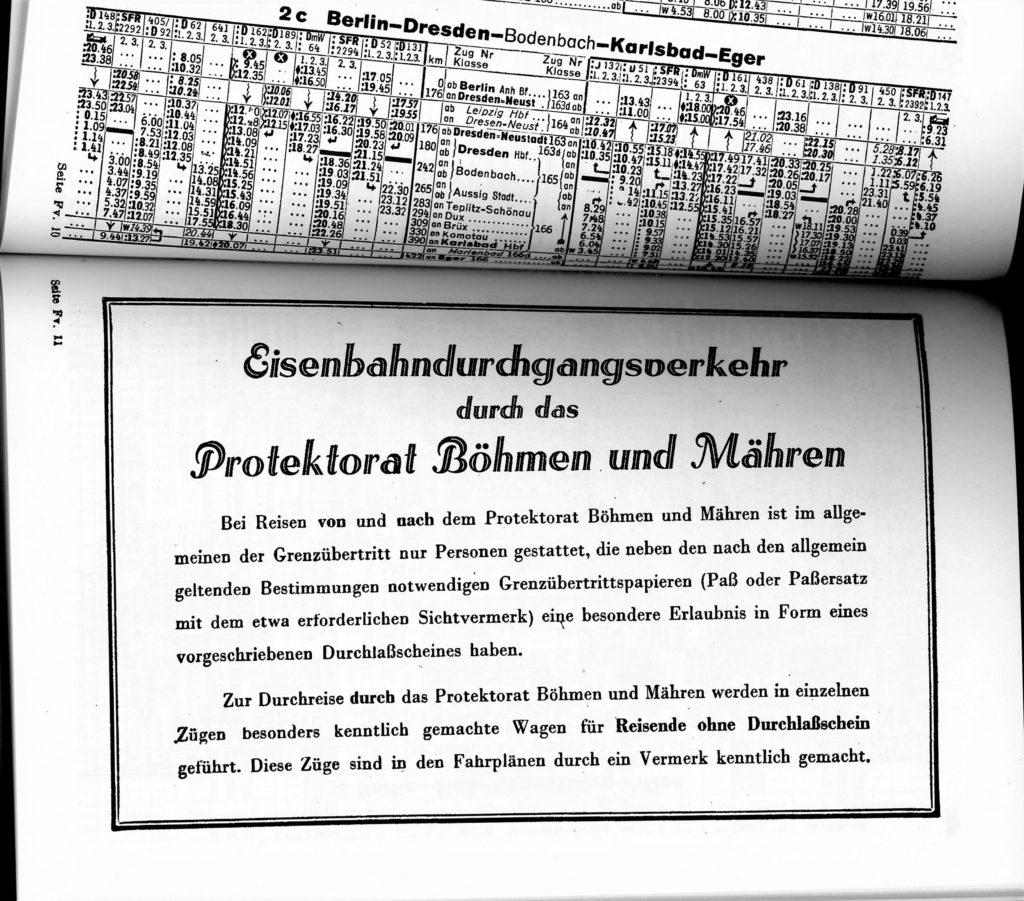

Though downplayed on an inside page of the 17 May 1943 “Official Timetable” of the Deutsche Reichsbahn , after four years of occupation the situation was still unsettled enough that special permission was still required for travel in or out of the Protectorate. Separate cars were marked for passengers riding through the former Czech Republic. This was not the same situation as in annexed Austria.

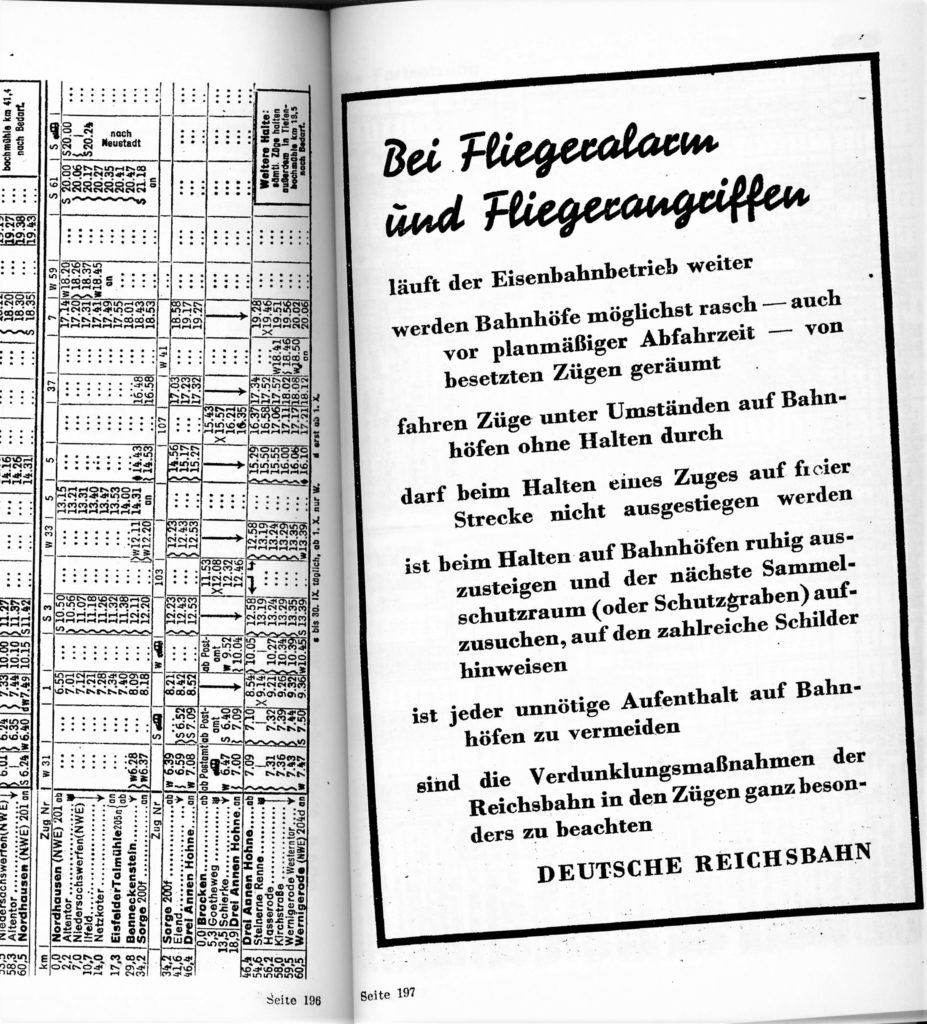

Aside from the hassle of border controls for a “vacation” in Prague by 1943 there was another hazard that the ambassador must have taken into account in his “mathematical certainty.” Living in Berlin he was to see more of the bombing campaign than in the Protectorate. Deeper in the “Official Timetable” for 1943 was a friendly reminder in a pleasant typeface that the Deutsche Reichsbahn was a target, but that the trains must go through.

Life in the Zehlendorf villa for Chvalkovský and his French wife may have reminded them of the old song “…only a bird in a gilded cage.” To the public they enjoyed diplomatic status in a fine home in an area infrequently bombed, even though the Reich government did not consider the Protectorate to have a foreign ministry. Privately, he was spied upon. His contacts with fellow Czechs drew suspicion. When his mother-in-law, living in Switzerland, grew deathly ill, permission for his wife to travel there required an okay from the Reich chancellery and the Protectorate and the Berlin police. In later years, their daughter Anita said that it was “a prison.” She had to return from school in Switzerland and check in every thirty days. Communications became more difficult as the war ground on.

In 1944 their daughter rebelled and did not return to grim Berlin. And in the continuing ironies, Chvalkovský was awarded the new medal created for the Protectorate in public recognition of his service.

The Honorary Shield of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia with the St. Wenceslas Eagle is a rare find for collectors today because within a year possession of it marked holders rightly or wrongly as collaborators. The last chapter of World War II was opening.

In January 1945 in a telephone call with Dr. Popelka of the Czech occupation government, K. H. Frank discussed protocol for which level of decoration was to be awarded Chvalkovský for his service. In the same call he learned that Popelka had not heard from the ambassador “in ages”, that the phones in Chvalkovský’s office were knocked out by enemy action, and that the ambassador was “not at his post” due to a nervous condition. [He may have remained in Zehlendorf at home, rather than at his office in a heavily-targeted area.]

February 1945 brought craziness to Europe with the “mathematical certainty” that the ambassador had forecasted. American planes bombed Switzerland, creating a diplomatic storm, military investigation, and apologies. Belgium was declared free. Budapest fell to the Red Army. Previously neutral Latin American countries piled on, declaring war on Germany. At the headquarters of the railway that had shuttled Chvalkovský back and forth between capital cities the accounting books for 1944 that showed so much revenue from Fourth Class fares to the death camps were closed. For the first time in the 24 years of the Deutsche Reichsbahn for 1944 there was no audit.

On February 22nd and 23rd of 1945, the Royal Air Force and the U.S. Army Air Corps unleashed “Operation Clarion” – a massive series of heavy bombing raids, mainly on small rail and road junctions between Berlin and the front lines. Then there was a pause. What was less noted was that on February 21st the RAF’s small Mosquito bombers began 36 days of night raids on Berlin.

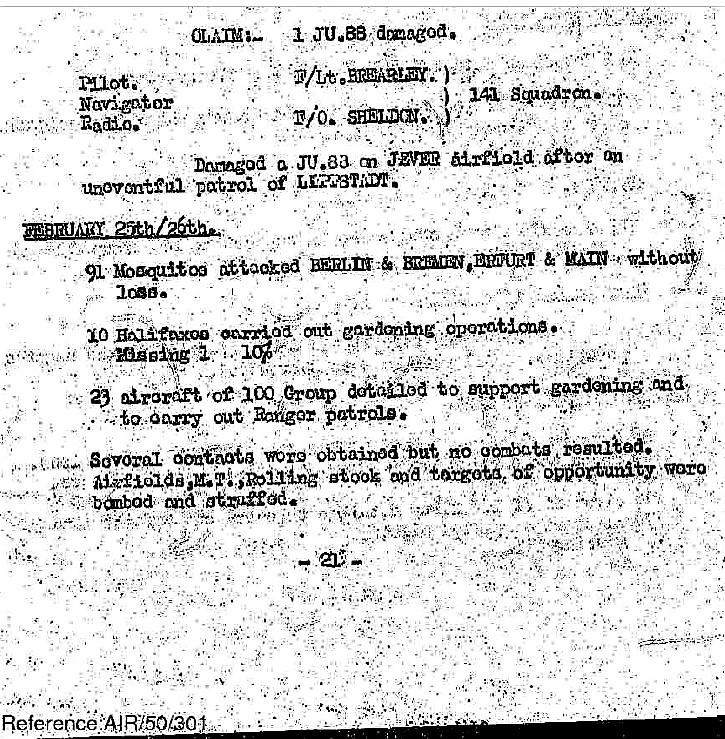

On the evening of February 24th four Mosquitos of Squadron 163 took off from RAF Wyton for a raid on Berlin. As part of the Night Striking Force they hit designated targets around midnight and turned quickly back to England. Then a weather front shut down operations across the Channel, creating a pause in the relentless pounding by the US and British forces determined to end the Third Reich.

Group 100 (Special Duties) was the bland name given to the Royal Air Force unit pioneering the most advanced air combat electronics. Its Mosquitos carried on “and targets of opportunity were strafed.”

At this point in the history of the villa we should note that there are very different versions as to what happened next. What follows is speculation based on the facts that are available. [Two other diverging versions are in the attached pdf.]

On February 25th, Ambassador František Chvalkovský and his wife Blanche set out from Sven-Hedin-Strasse 11 to the west or southwest of Berlin by car, heading toward Switzerland. She had documents permitting travel into that neighboring country. It is not clear whether the ambassador planned to drive her there and then return to his post or whether he intended to remain in Switzerland. They may have decided to travel by night. Day or night, there was little private auto traffic on the road due to stringent gasoline rationing. To a British pilot their car would have seemed to be a government or military official vehicle. A short burst of fire from the Mosquito’s Browning machine guns would have — in the airmen’s minds — eliminated one more Nazi big-wig.

Ambassador František Chvalkovský was killed, whether by bullets or metal fragments or the consequent crash. His wife was severely injured, including passage of a bullet or metal fragment through her mouth. She was taken to the hospital in Belzig, about 45 miles (70 kms) from the Sven-Hedin-Strasse.

Even as the Allied vise closed around remnants of the Third Reich, procedures were followed. By the 27th of February Karl-Hermann Frank in Prague had received a report of the attack from the Reichs Chancellery in Berlin and notified the Reichsprotektor Dr. Frick who was in Bavaria at the time. Reports of the attack were in newspapers the next day.

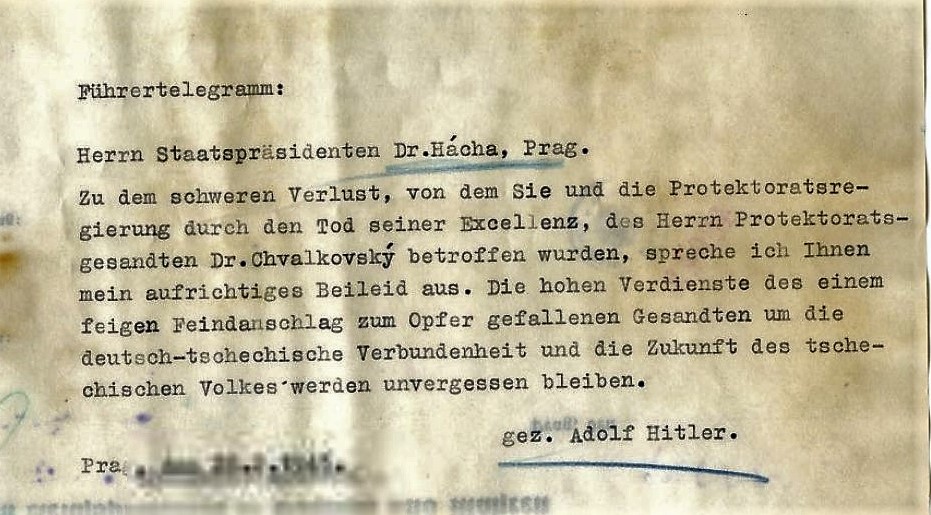

On the 28th Adolf Hitler telegraphed his regrets to President Hácha and that message was published the following day, along with Hácha’s thanks and messages of sympathy from the leading actors in the German occupation. There was an irony in the sympathy from K. H. Frank, who had been so unhappy about Ambassador František Chvalkovský’s role as an alternative link with the government in Berlin.

In Berlin, Legation Secretary Dr. von Schebec took on the responsibility of contacting daughter Anita Chvalkovský. As information flowed back and forth it was noted that the legation could be reached at Sven-Hedin-Strasse-11, rather than at the Kurfürstendamm office.

On the 2nd of March, as described in the travel orders at the beginning of this article, the body was returned to Prague. Frank received regrets from top officials who were unable to travel but sent memorial wreathes. The Führer sent a wreath. The service was set for the 13th at a crematorium at 4:30 p.m.

On March 19th Frau Chvalkovský was reported to have been moved to the Swiss ambassador’s country home west of Berlin to recuperate. She was still in great pain. On March 27th there was no change. Around them the Third Reich was crumbling. After an argument on March 28th Hitler replaced Heinz Guderian as chief of the general staff with Hans Krebs but gave Krebs no leeway to make decisions. Hitler shifted units away from Berlin to defend Prague. On that same day a Hamburg newspaper reported the Chvalkovský funeral, two weeks after the event. In Sven-Hedin-Strasse people scrounged for food and listened to the BBC.

The wounded Chvalkovský was last reported on April 11th to have reached a convalescent status in Kissleg im Allgäu, only 17 miles (27 kms) on back roads to the Swiss border. She had the permission to exit Germany.

At this point the story becomes clouded by the fog of war. Anita Chvalkovský having left Switzerland was apparently arrested by the Germans and later was released. She made her way through the chaos to the villa (her recollections say to the embassy, but that seems improbable). She may have been attempting to obtain family items that were left behind in Sven-Hedin-Strasse 11. According to her recollections she distributed the cache of food items there to the remaining staff. Her harrowing story and her transformation to a glamorous life as the actress and entertainer Nyta Dover is outlined in a *.pdf attached to the next page.

In 2018 this writer visited Prague. It thronged with tourists enjoying the architecture, the museums, the music, the food. It was difficult though not to reflect on the decision made by Ambassador František Chvalkovský to accept the 1939 Hitler ultimatum in order to spare the residual Czech lands a crushing war. We can analyze his actions in the light of what followed but must consider another statesman’s point :

“The analyst can choose which problem he wishes to study, whereas the statesman’s problems are imposed on him… The statesman is permitted only one guess, his mistakes are irretrievable.”

Henry Kissinger in Diplomacy, 1994