American and British residents of West Berlin occasionally heard news of their fellow citizens who lived on the other side of the Berlin Wall. In 1971, a small news article reported the death of classical singer Aubrey Pankey. His life provides a look at what Berliners called “Darüber” — “the other side of the Wall.”

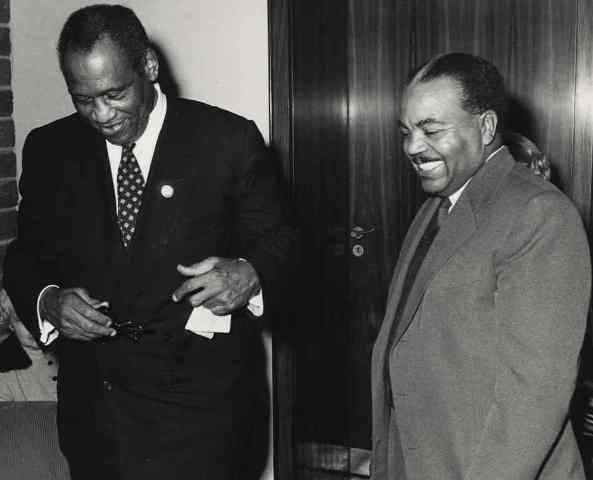

Americans Paul Robeson and Aubrey Pankey admire birthday cake for Robeson in East Berlin. [The 1960 photo above is from the archives of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin. It may not be reproduced beyond this website or student purposes without their permission.]

A minor item that turned up in my notes from Berlin reminds one that there were two sides to the Berlin Wall. Of course there were Berliners and East Germans who ended up on the “East” side by accidents of history. But there were also people who chose to live there for various reasons. One of them was Aubrey Pankey, American.

On a Sunday, May 9, 1971, his life ended in a traffic accident in suburban Teltow, in East Germany, or as he knew it, the German Democratic Republic. Teltow was on the other side of the Wall canal of the same name, a place where the light of flares launched to illuminate possible refugees trying to reach the American Sector could be seen from our barracks. Irony was common in divided Berlin; this man died far from home, but within a few minutes’ drive of hot dogs and Coca-Cola. Of course, a person would have had to be willing to take the chance of dying in order to make a trip through that wire.

There were many reasons that led American and European intellectuals and performing talents to end up in the German Democratic Republic. According to the official GDR governing party’s Neues Deutschland, the 65-year old artist had been living in the GDR since 1956. Intrigued by this item, three decades later I visited the handful of websites where Pankey’s name appeared, and followed up on the handful of references to him in the wide-ranging Denver Public Library and Berlin public library collections.

Maud Cuney-Hare chronicled his early years in her book, Negro Musicians and Their Music. Born in 1905 and a native of Pittsburgh, Pankey’s natural gift for singing was identified early enough to lead him to voice lessons in Boston with private teachers. He had been studying to become an engineer. A January 26, 1930 recital “…evoked such critical praise that he was determined to go abroad for further study. His pluck and courage in the face of continued financial obstacles won friendships for him, and in 1931 he was in Vienna studying voice.” In 1932-33, he achieved success in the artistic swirl of pre-Hitler Berlin, and again he went back to Vienna, where he continued to perfect his singing.

According to Cuney-Hare, critic Robert Konta in the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung of November 26, 1931 wrote of him as a “…a black man who sings Schubert and Richard Strauss with an overwhelming intensity of feeling and forms them into great unforgettable experiences. He is a boon for our period where one is very easily inclined to see in all Negro musicians mere Jazzband Clowns. There are evidently black men who are messengers of culture at its greatest.”

Josef Reitler of the Neue Freie Press on the 23rd of that November wrote “He is the possessor of a musical soul, which in glowing manner is able to approach Schubert and Richard Strauss with a feeling and understanding worthy of a born German. Colorful expression is skillfully combined with a natural mellowness of voice.” Cuney-Hare placed him in Vienna as of her writing.

Pankey’s reputation spread. Walter Nhlapo, writing an article “Drama vs. Jazz” in the Bantu World of 22 Jun 35 called him a “…famous Negro man…” in the same list as Paul Robeson, Duke Ellington, Marcus Garvey, and Booker T. Washington.

Outside the bright circle cast by the glowing light of his career, the world turned ugly. Left wing and right wing political gangs attacked each other in the streets of the European cities, and yet in some ways, he would have been a freer man in that setting than had he remained in the United States. European racism took different paths than in the U.S., and the Europeans’ high regard for classical musicians would have insulated him from some of the problems that might otherwise have arisen. But he could not have helped seeing what was happening.

His 1934 portrait photo, available in the Marian Anderson Collection at the University of Pennsylvania, shows a thoughtful young man. The photo was taken when he performed in Paris, in a year when anti-parliamentary leagues attacked the leftist government in spiteful words, and attacked its democratic citizens with their fists and jackboots. Backed by right-wing businessmen who envied the efficient new Fascist government of Italy, the violence created an atmosphere in which the intellectuals who crowded cafes of the City of Light felt the need to take extreme stands. Over 8,000 intellectuals were swept into the “Anti-Fascist Common Front” and by the end of the year, the Popular Front political coalition was developing, blurring the distinction between Socialists and Communists in their unity against the threat of Fascism. The political center collapsed.

[For a detailed description of the mid-1930’s environment in which Pankey was immersed, read William L. Shirer. For day to day life in a Paris neighborhood, read Elliot Paul.]

Back in the U.S. during World War II, the baritone singer performed in a variety of venues in the U.S., with some performances linked to Left political causes made “respectable” by the war against right-wing dictators. So had many other people who did not choose later to emigrate from the U.S., but they did not necessarily have his exposure to the over-wrought politics of Europe. During this time, he was featured on a cover story in the Musical Courier.

As an African-American, he would have been caught in the organized and legally-sanctioned discrimination that marked the nation in which he grew up. Married to a white woman, Katherine Weatherly, shortly before the May Day 1945 Concert in New York City in which he performed, he would have experienced the highs and lows of a man passing in and out of the almost bewildering variety of written and unwritten rules that governed relations between the races. This network of harassment was especially difficult on performing artists, as local custom was a big part of the segregation system. Opportunities to tread on local sensitivities were many. Still, he recorded a program of classical music for the Voice of America.

Pankey continued to tour overseas, as well. Searching the Lexis newsfile database brings up only one “hit” on this man’s career:

Southland Times, New Zealand

MARCH 14, 1949: “The first of his race to be heard for some time in Invercargill, Aubrey Pankey, American negro baritone, impressed a well-filled house at the Civic Theatre on Saturday night as a singer with unmistakable authority. Confident in his approach and wholly relaxed in his bearing, he revealed a deep and unsuspected capacity for sensitive expression.”

Pankey continued his career and he and his wife engaged in Left politics in the post-WWII United States. The information that I have found easily accessible is piecemeal, but in New York Times accounts, he had settled in Paris in 1948, but was expelled from France in 1953 for his campaigning on behalf of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, convicted of spying in the United States for the Soviet Union. [rwr note: Given that France had a large Communist element of its own, including elected officials, I would like to learn more about this process, suspecting that there was more to it than what was stated in his short obituary.] In the early 1950’s, his wife worked for UNESCO, where she was fired with colleagues for there being a “…reasonable doubt…” as to their loyalty to the United States. Subsequently, in 1955, a UN tribunal ruled for the first time that this was not a requirement for that organization, and awarded her back pay. If this seems like a confusing period, it was.

[For a description of Paris life, including the overlapping political and intellectual worlds, read Stanley Karnow.]

In October of that year, Aubrey Pankey was named by a U.S. official as being one of the American political self-exiles living in Czechoslovakia. However, in the New York Times obituary relayed from Reuters, published on 11 May 71, friends stated that he had lived in East Germany “..for the last 17 years.” The accident story, from ADN, the East German news service, published in Neues Deutschland, stated that he had lived in the German Democratic Republic for 15 years. This may be based on earlier GDR newspaper clippings in the ADN files, which stated that Aubrey Pankey had lived in the GDR since 1956. His wife survived him, according to the New York Times-Reuters obituary.

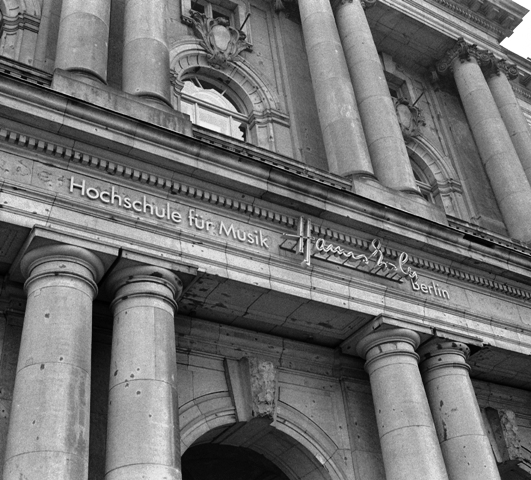

In the GDR, he recorded for the Eterna label, the East German classics line and made public appearances as a singer. He continued touring performances, and worked as a Docent at the German High School for Music in Berlin. [A Hochschule in German is an advanced school teaching specialties at the collegiate level.] His musical repertoire was reported to include Kunstlieder (art songs), segments of musicals and operettas, Volkslieder (folk songs) and, of course, what the Germans called Negervolkslieder (Spirituals, work songs, folk songs of Black Americans.) A reference in In Black and White (Detroit, 1980) indicates that he also painted and developed skills as a photographer, composer and teacher. In an interview published in Freies Wort for Pankey’s January 1968 performance in Suhl, publication of his children’s book “Firebird” (Fuervogel) was reported.

For a side-trip into the story of Aubrey Pankey’s era in obscure Suhl in Thuringia (southwestern East Germany), click on: Winding Road to Suhl: Aubrey Pankey

With his earlier background in Berlin and Vienna, he would have had a better chance than many expatriates at fitting into the environment of the GDR. On the other hand, the limited information in the Internet and his obituary infer that his career had faded at the end. He appeared in a 1970 Hungarian film: Meteorvada’szok, which was based on a 1968 book by GDR sci-fi bestseller Carlos Rasch. In the same year, a GDR-Polish release based on another Carlos Rasch story included Aubrey Pankey as a scientist on board a space ship in Signale – Ein Weltraumabenteur. He lived a quiet life with the other expatriate artists and political figures, comfortable by East European standards.

When he set out on the road through Teltow, not far from the Babelsberg film community, was his 15 to 17 years of exile wearing thin? The information that I have found so far raises more questions than answers. Some facts about his last night may be found in A Small Death in Germany.

–rwr–

Robert W. Rynerson Denver, Colorado

2 Aug 01 – updated 5 Sep 09 – 26 Aug 19

Note: since this initial writing, much has been added to Wikipedia information regarding Pankey’s overall music career and public political activities. Information regarding his personal life is still sketchy — in particular his marriages and the extent of his relationship with accompanist Fania Fénelon — and may be questioned.

====================================================

A look back at Paris as the home of African-American Expatriates

Writing for Cox News Service, Bert Roughton, Jr. described the role that Paris played for African-American intellectuals, as he reported on the French government’s decision to specially honor Josephine Baker:

“She [Josephine Baker] was perhaps the most prominent among the community of black Americans who flocked to Paris throughout the past century, drawn to the city’s reputation for embracing them.

“Indeed, while many blacks felt inhibited in America, the creative and social freedom of Paris proved irresistible for artists, performers and intellectuals. Writers Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, Jessie Redmon Fauset and Countee Cullen moved here, as did painters Romare Bearden and Henry Ossawa Tanner. Along with Baker, musicians Sidney Bechet and Ada “Bricktop” Smith thrived in the jazz-crazy French capital.

“In the 1950s, American blacks turned the decision to move overseas into a political statement. Some of the most influential black writers of the time– including Richard Wright, James Baldwin and Chester Himes– settled in Paris, declaring that U.S. racism was intolerable.

“While the ’20s were the age of jazz in Paris, the ’50s were the age of literature.

“With the possible exception of New York, no city in America could rival the collection of Black literary talent along the banks of the Seine during those years,” [author Tyler] Stovall wrote.”

- – – from the Rocky Mountain News – 3 Feb 01

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was active in Paris in the 1950’s and among the agency’s subjects were the activities of expatriate African-Americans.

Comment by John F. Fox, Jr., FBI Historian, Office of Public Affairs at Wilson Center conference, Washington, DC. – 31 Mar 2017.

https://www.c-span.org/video/?426298-2/francoamerican-dutchamerican-intelligence-exchanges (about 29 minutes into video).

====================================================

Bibliography:

ADN [the German Democratic Republic’s news agency] newspaper clipping file in the Zeitungabteilung of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin / Preussischer Kulturbesitz; Westhafenstrasse 1, 13353 Berlin.

Visit: www.sbb.spk-berlin.de/ .

Agee, Joel; Twelve Years: An American Boyhood in East Germany (Rev. ed.). University of Chicago Press; ISBN9780226010502; 2000.

Cuney-Hare, Maud; Negro Musicians and Their Music; The Associated Publishers, Inc.; Washington, DC; 1936.

Eischeid, Susan; The Truth About Fania Fénelon and the Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz-Birkenau; Palgrave-Macmillan an imprint of Springer International AG; Switzerland; 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-31037-4.

Karnow, Stanley; Paris in the Fifties; Times Books, a division of Random House; New York and Toronto; 1997; ISBN 0-8129-2781-8. Random House http://www.randomhouse.com .

Paul, Elliot; The Last Time I Saw Paris; Random House; New York; 1942. Also, Macmillan Company of Canada Limited; 1942. [Pre-WWII Paris.]

Paul, Elliot; Springtime in Paris; Random House; New York and Toronto; 1950. [Post-WWII Paris.]

Popek, Pete; in Newsgroup rec.collecting; 1998/10/07; Oneonta, NY; stated that Musical Courier had carried cover story with photo of Aubrey Pankey in the 1940’s.

Shirer, William L.; The Collapse of the Third Republic; Simon and Schuster; New York, NY; 1969. [Pre-WWII Paris.]

Stovall, Tyler; Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light; Houghton Mifflin; Boston; 1996; 366 pages; ISBN 0-3956-8399-8.

For more, click on the Aubrey Pankey Links Page.