Snow and cognac in March 1971

Remembered in March 2007, by R. W. Rynerson

The return of gray weather here in Denver reminded me of the bad cold that I picked up in Hamburg in March 2005, but then some questions from a colleague reminded me of another trip, in March 1971, on which the sun shone, a cold was cleared up, the Mediterranean was deep blue, and a few dollars went a long way. In fact, I realized later that it was part of my best 24 hours on my own outside of Berlin. Unfortunately, my handy Voigtländer folding 35mm camera went out of order, and I bought a Spanish Kodak Instamatic for this part of the journey.

The pictures that you are about to see are scratchy, the color is starting to vanish… but then so is the way of life that I briefly experienced. The day began as an interesting bit of itinerary and ended with a profound experience. Every Berlin veteran must have a leave story to tell; the “O. Henry ending” of mine caught me off guard.

After circling through some of Mediterranean Spain, I found myself in the old station in Zaragoza. (It is shown in the current issue of Passenger Train Journal next to the recently opened huge replacement station.) I had arrived there the day before on one of the tilting, streamlined Talgo trains, not knowing that I could have waited thirty years more and then traveled on that type of train between Portland and Seattle. There were other things to see, though.

Spain had just discontinued 3rd Class (!) rail travel, and I was catching the morning local train up into the Pyrenees, to the French border, a train which still carried a 3rd Class wooden coach on the tail end.

It turned out that the way they discontinued 3rd Class was to repaint the signs on the best of the 3rd Class cars, so that they were now 2nd Class (at the higher fare). In the interest of my education, however, I joined some local people on the wooden benches in this car and bumped along with them for about an hour till the conductor came and told me that this car would be taken off the train at Huesca, the last real city in Spain on the trip.

When I moved forward into 2nd Class, I felt satisfied at the thought that my brief experience with 3rd Class might be the most interesting part of the ride, but it became more interesting as the train climbed. Somehow, I had the idea that the Pyrenees were not that big a deal. As the track began to twist and turn, I started to change my mind.

And then, tantalizing at first, some of the turns revealed a massive front of mountains ahead. Snow was blowing in clouds off of them. In the foreground, the train continued making stops at tinier and tinier villages.

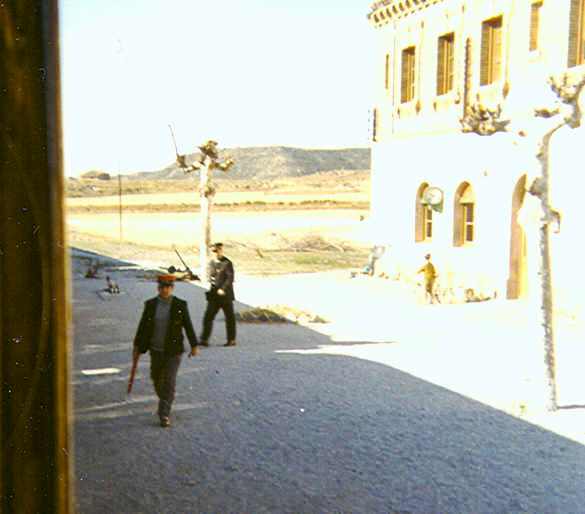

In these villages — it was Sunday morning — life barely seemed to exist. The photo above shows an 18-year old (approx.) woman who alighted from the train in this tiny village. She was dressed as plainly as the much older women in my 2nd Class compartment who told me that I should save my film for the really beautiful part of the trip ahead.

In remembering how this landscape intrigued me at the time, I realize now that growing up in the Pacific Northwest and living in Germany in the Army, I really did not know much about deserts or drylands. I saw that as the train climbed, we were following a series of dams and lakes that stored up snow melt run-off for use in irrigating the otherwise bleak farmlands of northern Spain.

I also remember how interesting it was to see so little population. Americans have the idea of Europe as being densely settled, but the villages here were tiny, as shown in my previous photos, and there were few of them.

Of course, this trip was only made three decades after the Spanish Civil War, and I could not tell how much poverty and underdevelopment was a legacy of long ago, or a consequence of the drylands, or how much was the result of that bitter struggle.

Only the night before, I had experienced some of the many reminders of the tight social control in the arch-conservative Spain of Generalissimo Francisco Franco. Earlier in the trip, I had run into more police inspections, border guard attention, and flat-footed hints of secret police activity than in any of the other countries west of the Iron Curtain that I had visited.

One of the things that I noticed about this train heading up into the mountains is how many young people were taking it for access to day hikes. Sometimes it was just two or three students, as in the attached photo, and sometimes it was a larger group of young men and women.

On the night before this train trip, when I arrived back at my hostal after seeing a film, I had to clap my hands loudly. Following traditional practice, a night watchman patrolled each street in urban areas. He had a big key ring with keys to the street gates of each house, hostal (Spanish for a pension or bed & breakfast), etc. The watchman appeared out of the shadows and let me in to my hostal. He had to receive a tip.

The watchman traditionally was a retired military person or civil servant. This provided him with a supplement to his government pension, but it also meant that someone who was dependent on the government knew everything that was going on in that street, including who came and went at each home.

As urban life became more complex, an informal call by police on the watchman was no longer enough. In 1968, the Organizacion Contrasubversiva Nacional was formed to give the Fascist government a real secret police department.

How did this relate to the students’ desire for fresh air? Outdoor sports and hiking were among the few socially acceptable outlets in which they could get away from the tight social controls and the political controls. No wonder these passengers looked so happy!

Passenger count gets thinner — as does the air

The passenger count on the local train to the French border continued to thin out, while the scenery became more and more dramatic. An elderly Spanish lady was amused at my picture-taking and told me to wait until we reached the higher elevations. Fortunately, I took her advice, because things were about to unfold in a way different than I had expected.

The train schedules in the Deutsche Bundesbahn’s Ausland Kursbuch (Foreign Timetables) France and Spain sections disagreed with each other slightly, but that was not unusual. The Spanish tables showed one set of times and the French tables showed a slightly different set of times. The train was running on a third set of times, but every source was within a few minutes of the other. (This is not uncommon when paper timetables have to be circulated between companies.)

As the train eased into the Spanish border station of Canfranc, I was prepared for the usual mad scramble to go through Customs while changing from the Iberian Broad Gauge Spanish train to the Standard Gauge French train. Instead, the few remaining passengers wandered off. No one headed into Customs.

I stopped for a moment to look around, and saw that the railway crew was getting ready to couple a standby car onto the equipment of my train to be ready for the Sunday afternoon return crowd from the mountains. I snapped the next photo as I looked at a scene that I would have thought was in old Colorado. The spare car had a wooden body and the mountains behind closed in on the little town.

Cautiously, I approached a Spanish officer in the tri-cornered hat of the Guardia Civil. Where should I go for the train to France? After he understood what I was asking, he laughed. He made some comment, but I couldn’t understand it. I asked if it was okay to walk into the Customs area, and he waved his arm to indicate that I was welcome. Cautiously, I walked into the room where baggage would have been opened. There was no one there. I walked a bit further and realized that I was headed out the French side. No one was there.

Stepping out onto the platform, I realized what the guard must have been trying to tell me. The following photo shows what I saw. The tracks were completely covered by snow. In some places, there were icicles hanging on the electric catenary. It was obvious that there would be no train coming. Was I at a dead-end?

In the distance the grand station structure that played the part of an abandoned Russian palace in the 1965 film ‘Dr. Zhivago’.

I stumbled through the snow to a hut from which I could see smoke rising. A lone SNCF (French) railwayman was going through the motions of tending the empty yard. As best as he could, he tried to explain to me that the line was closed by what I misunderstood to be a storm or a washout, but that a bus would be running. I walked back through the snow, still half expecting to be yelled at by a policeman or a border guard, but nothing happened.

[I was to learn later that this was the beginning of a controversy that continues to this day. A train wreck in 1970 had destroyed a French bridge. It has never been repaired. Critics believe that the railway authorities seized on this “fortunate” coincidence to close the lightly traveled line. Governments have instead poured millions into parallel roadway construction projects claimed to spur economic development, to little avail.]

Back in the station, I looked around until I found the waiting room and an SNCF ticket counter. Posted there was an emergency timetable, showing a bus connection between Canfranc, Spain and Bedous, France. Bedous was so small that it did not even show on my German timetable. Instead of a mad dash to catch the French Marchandise et voyageurs (Mixed freight and passenger train) I was going to have over two hours in Canfranc.

I thought of buying more film, as I only had a few frames left. But it was Sunday, and in conservative Spain almost everything was closed. The one store that sold film, I was told, was among the places closed.

So, I headed into the station restaurant to get some lunch and pass the time. And that was the beginning of getting to know a bit more about the people of the Pyrenees.

Dining and then a stroll in the snow

The railroad station restaurant was huge, with tables set with white tablecloths for perhaps over 100 customers. There were three or four customers in the place. A television was running in one corner with live, beginning-to-end coverage of a Catholic religious procession. The hostess seated me at a table with an older man who was dressed like a rural Basque who one might see in Oregon or Nevada. By now, I had been in Europe for almost two years, so I was not surprised at being seated with other people, but what followed was not typical.

I didn’t order wine with my meal, but my tablemate simply ordered another glass for me and poured some of the wine from his bottle. We broke bread together with me saying my few words of thanks in broken Spanish. Otherwise, we said little, but it broke the ice. It turned out that he would be on my bus.

When it came time to load the bus, I found that it was the 11-passenger Citreon all-purpose vehicle one saw everywhere in France then. These were used as police vans, as station shuttles, as delivery trucks, anything that one might imagine cutting into their sheet metal bodies. A photo was snapped by the bus driver, and I look a little goofy in it, but you need to have an idea of how we were going to assault the summit of the mountain pass dressed in clothes for a short train ride through a tunnel.

The Garage del Val d’Aspe bus had been chartered by the SNCF for us. The company name, a mixture of Spanish and French, was typical of the language spoken there. The driver had brought a buddy along, which turned out later to be a good thing. As we pulled out, though, I was concerned to see how both of them smoked and waved their hands while driving the two-lane mountain highway. Later on, I learned that this was the highway that Hannibal had taken with his elephants on his epic march to attack Rome. I wondered if his drivers paid better attention to the road.

Just before departure, a well-dressed Spanish man arrived and said kissy farewells to a VERY well-dressed French woman, presenting her with a bottle of Spanish Cognac. We others gawked: a teen-aged girl, an elderly lady, two downscale Spanish guys, and my ‘Basque’ tablemate, none of us so glamorous. I looked around at the drivers and our diverse bunch of passengers, realizing that we had now completed casting for a Hollywood ‘disaster’ movie.

In a few minutes, we were passing into deep snow, and in what seemed like about half an hour of driving, we were stuck in the snow, on the cliff side of the icy highway. When we got out to survey the situation, we found that if the driver tried to rock the bus back and forth out of the snow, our bus might go over the edge.

This being conservative Spain, it was decreed that the men would get out and push the bus, while the women remained inside it. I felt safer outside. We made little progress, and it was decided to chain up the bus. Now I understood why the driver’s buddy had come along. I also learned what the large plastic sheet in the back of the bus was for. The driver and buddy took turns on the ground on the plastic sheet messing with the chains.

I was designated to be the flagman for this project, since my Spanish/French was of little help. I would shout “Attencion!” in a combination of languages when the occasional other vehicle came by, so the man chaining up could get his legs out of the roadway.

With the chains on the bus, we male passengers and the driver’s friend all pushed, and the bus rolled free of the snowbank and ran ahead to a flatter spot. I found myself walking briskly along in the snow in street shoes and in the raincoat I had brought for Spring weather. I noticed that I was getting ahead of the older men, who took it easy, and then I noticed that the altitude was getting to me. I had expected to go through this part of the trip in a train passing through a tunnel, not go mountaineering.

The next photo shows us catching up with the bus. You can see a snow pole on the left side of the road to show where the edge was. The man with the hood pulled up on his jacket is my ‘Basque’ friend. By now, we were all old friends, and back on the bus, I pulled out some hard candies that I had carried along. Everyone was glad to have one, but then I had to laugh: the elderly woman said, “of course… American soldiers always give out candy!” I had perpetuated a stereotype.

A few minutes later we passed what the Spanish considered to be snow-fighting equipment — a flatbed truck with a blade plow on the front. Then we entered a ski area, enlightening to me, as I never knew that Spain had skiing. We lost more time trapped in crazy traffic jams in the resort.

At one point we watched a couple of men build a snow pyramid to hold a 35 mm camera. Then a whole group of skiers formed up, their photographer started the self-timer, and ran to get into the group shot. At that point, traffic started to move and our little bus pulled between the camera and the group. The shutter clicked and they got a close-up of the side of our bus. I was glad that my Spanish was so limited, as I don’t think that the things that the group of skiers was shouting at our driver were nice.

The bus climbed further, and soon we were rounding a curve that revealed a massive fortress blasted into the rock facing France. With my Army experience in Berlin, I found myself counting trucks and equipment. Was France going to invade Spain? They last time they had done that was under Napoleon, as best as I could recall, but I guessed the Spanish were not taking chances.

I assumed that the border was coming up, after all our hairpin turns, and there it was. One last reminder of Franco’s control of Spain was coming up.

Last stop in Spain

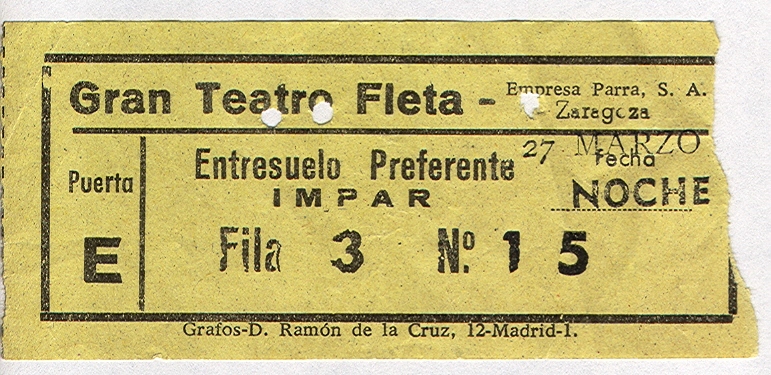

Here were the last hours of March 28, 1971, the end of my week in Spain. No, I don’t always remember exact dates from that long ago, but I found a movie ticket with some other items from the trip. The evening before my bus ride over the Pyrenees, I had watched Paint Your Wagon in Spanish, starring Lee Marvin. The part of the mayor in an old Western town was played by Tom McCall, who was then actually the Governor of my home state of Oregon. The Spanish crowd cheered and shouted “Toro, Toro!” for the scene in which a bull rampaged through the movie town. It was strange and endearing at the same time.

All of that, in dry Zaragoza, seemed far away that next afternoon in the midst of the snow and ice at the border crossing. The Spanish customs post did look like it belonged in a movie, however. It was perched on the edge of a cliff into which the two-lane roadway was cut. There was little room for any traffic or inspections, other than in the road. A red-and-white customs barrier blocked the road as the border guards of Fascist Spain waved us to a stop.

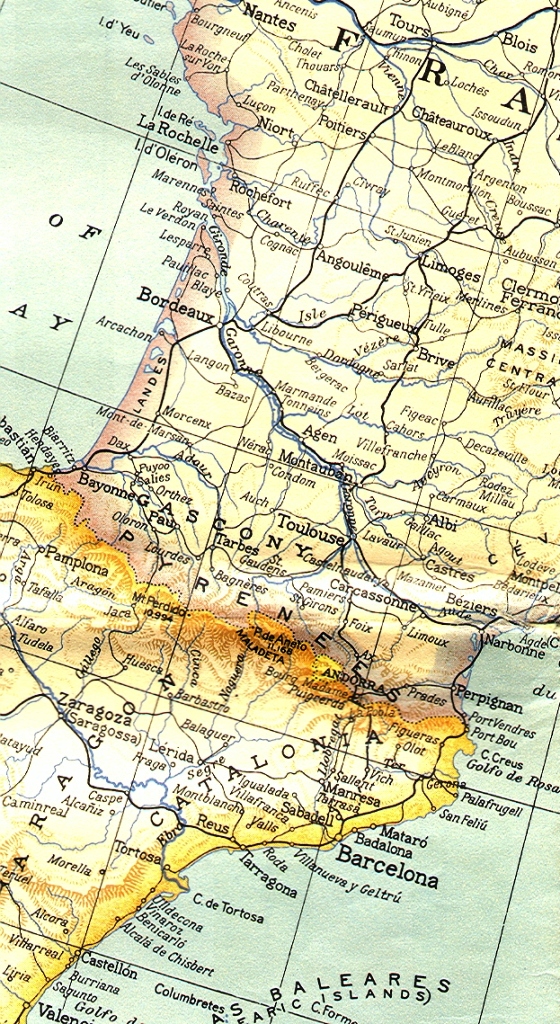

On a 1938 map, the rail line is shown as a black line crossing the border west of Mt. Perdido (10,994 ft). From breakfast time, I had started on this map in Zaragoza, passed through Huesca, and in mid-afternoon was at the crossing.

The guards and the driver/s had a long discussion about the events of the day and then we presented our papers. On previous European border crossings, I had tried only presenting the relevant documents, and then the officers would ask for more. This time I pulled out everything, and it made quite a pile of paper:

+ Portugese language orders

+ Spanish language orders

+ French language orders

+ Berlin travel documents, in Russian, English and French

+ Army DA31 Leave and Pass Form

+ My Army identity card

You can read more in my webpages on the paperwork that we soldiers generated at: Berlin 1969: Documents.

The border guards pounced on the Russian language document. My travel orders had been stamped by the Soviet Army when I left Berlin via their checkpoint Marienborn. I was a bit nervous, because the losing side in the Spanish Civil War had been involved with Soviet (Stalinist) “advisors” and “volunteers” and these guards worked for the winning side (that had been involved with their German Nazi and Italian Fascist equivalents). They studied the document carefully and then I saw them flip it over and on the back was printed a purple reproduction of our Berlin Commanding General’s signature and rubber stamp.

I think that they were reading the French text with the signature. Everyone else on the bus was getting waved through, so they could watch with me as the guards’ lips moved while they read the Berlin travel authorization. The guards were now impressed, and in turn, everyone on the bus was highly impressed. One of the border officers returned my paperwork with a smart flourish and a salute. One of them also explained that it was a pleasure to pass through the “first American of Spring.” I breathed a sigh of relief.

The red-and-white barrier was raised and we were rolling downhill. Around a curve, we saw a French fort cut into the rock walls of the next cliff, facing Spain. They were ready with a mirror-image of the fort I had just seen on the south side of the pass in case the Spanish invaded them.

I kept wondering where the French border post would be. In the meantime, we suddenly began making good time. Unlike the lone Spanish blade plow, the French were using an elaborate snow and ice clearing vehicle that scraped the road bare. Our driver continued his conversation with his buddy, waving his cigarette with one hand, while steering down the mountain pass with the other. I tried not to think of those little news stories in the back of the papers, headlined “Bus Plunges Off Cliff.”

The French border post finally appeared in a pleasant mountain valley setting, far inside their country. Our driver used their phone to call the railway dispatcher and then reassured us that they would hold our train. I couldn’t believe that, but hoped he was right. There was no excitement about my paperwork here– the French barely paid any attention to it and waved us all through.

Further down the valley, one question was answered as I looked down and saw what looked like a washed out bridge on the railway. This apparently was where it was shut down.

Picturesque village… and a realization

And then we were in tiny Bedous, not shown on many maps, and there was the SNCF station, with snow-free rails, and– our train was gone. The teenage girl of our bus group left to visit her friend in town– this was the end of the line for her. For the rest of us, it was cold, and an icy stream bubbled nearby. Picturesque, but we were getting tired of picturesque.

Instead of being a disaster, this turned into one more surprise. The Chef de Gare (Stationmaster) took pity on us and invited us to join him in his heated office (the waiting room was unheated). He was a jovial host and we all conversed in the local mixture of Spanish and French, with me being able to make out that the stationmaster had held the same rank in the French Army that I had in the U.S. Army. This immediately made us comrades in arms, although of different generations. Someone suggested that we should toast that, if we had something to drink.

At that point, the well-dressed woman who had attracted everyone’s attention in Canfranc reminded us that she had the bottle of Spanish Cognac that she had been given. She went to her bag to pull it out, and while she did that, to my American amazement, the stationmaster pulled out enough shot glasses from his desk drawer for all of us. Americans would not be surprised to find extra coffee cups in a stationmaster’s desk, but shot glasses caught me off guard. The last photo in this series shows us celebrating our adventures of the day, the French and U.S. Armies, the SNCF (even the dispatcher who had decided to send the train out without us), and whatever other excuse we had for finishing off the bottle.

The Cognac was powerful! I went outside into the cold for a while and walked along the banks of the creek to stop my head from spinning. That photo was the last frame on my Kodak Instamatic film and it was getting dark. I supposed that we would sit around in the station till the next and last train of the evening departed.

Instead, this day would not quit surprising me. The Spanish guy on the right in the group photo had been trying to get the attention of Our Lady of the Cognac. He suggested that they go into town and get a bite of supper. She responded by agreeing, but added that they should take “the American soldier” with them. Another one of the Spanish men volunteered to join us. And so, as the sunlight turned off behind the mountains, we walked down to the little village center with its crooked streets that looked like a Hollywood film set and found a busy inn that was serving dinner.

It was a simple, but good meal, but what I recall best, besides being amused at being the chaperone for this group, was the television news.

The War Was Televised

On French television, I found myself watching film of a column of GI’s passing through a swamp in South Vietnam, water up to their necks, holding their rifles over their heads. My new companions carried on their conversation, but I sat there with my head spinning. It was no longer the Cognac, but rather the weight of the realization that I was not only not going to Vietnam — something that everyone including me assumed when I went into the service in 1968 — but that I had learned so many things and was only five to six months away from finally getting out of the Army.

(I had left home after my leave on January 3, 1969 and was not to return home again until September, 1971. I had used all of my leave for travel in Europe, sure that I would soon be ordered to Vietnam, with a leave at home on my way from Berlin to Southeast Asia. Those anticipated orders never came. Later, my father called my time in Europe “the master’s degree you didn’t get because of the draft.”)

We finished our meal and met the others back at the train station. The train was an “emu” (electric multiple unit) set that had open seating, very much like a North American commuter train. We sat together and continued our multi-lingual conversation, while other passengers gawked openly at us, trying to figure out who we were.

The Chef de Gare stood on the platform and blew his whistle to signal the engineer to proceed, and then as our coach rolled past him, we waved; he saluted us military-style. There was an elderly lady watching us whose mouth dropped open when she saw that.

In busy Pau where the Bas-Pyrenees main line cuts across from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, our group split up. Some were destined there, some were transferring east toward Lourdes, and some — as I — were transferring west toward Bordeaux and on to Paris.

The Cognac lady smiled at us and headed for a comfortable sleeping car. The two Spanish guys who had been trying to get her attention headed somewhere back in the long string of 2nd Class cars. I found a 2nd Class car marked for Paris-Austerlitz and wedged myself in the corner of a compartment so I would be able to sleep. For a time, I was alone in the compartment, reflecting on the experiences of this amazing day and on the changes that I had experienced in myself during my two years in Europe. Then a group of French sailors stormed into the compartment at Bordeaux. Sea air blew into the open window as we rolled out toward the Loire and Paris and I thought of home and the Oregon Coast. The crowded Pyrenees Express seemed to be part of a different world as it hustled us into that night. –-rwr—

Postscript:

While my story above describes what I thought at the time, much more was happening. In the following excellent website, the story of organized neglect for the French (SNCF) part of this rail line is described. The French portion of the line has been temporarily shut down since the year before my visit till the time of this writing in 2007 and an update in 2012. As we learn, there is no money for this low productivity line.

Via the Wayback Machine

The old road over which our polyglot band of travelers journeyed in March, 1971 has been superseded, first by a bypass of the ski area, and then by a new, high-speed highway and tunnel. A colleague of mine, wise in the ways of the highway lobby, immediately guessed that the new highway was supposed to bring “economic development” — Europeans being no smarter than North Americans when highway money is waved in front of them. So, in a place where there is allegedly no money for restoring the out-of-action rail line, there is massive funding available for a road that has contributed to the dramatic growth of long-haul truck traffic between the Iberian Peninsula and France. The following English language link discusses this issue.

Pyrenees Freight Transport.

Wikipedia in French, with a view of the vandalized ruins of the great station at Canfranc: Wikipedia French .