15 Nov 69

On the right side of the photo, riot police line building fronts to prevent break-away groups from smashing show windows.

Return to Demonstration – 15 Nov 69.

Scroll down to continue with photographic coverage of the demonstration.

This photo from Gneisenaustrasse was damaged in my attempt at film processing, but it is the only frame that I have showing this group. Is someone in this photo now an influential figure in the Palestinian movement or did these students end up settling in Germany?

Although a march can be exhilarating for the marchers, it can be at least a nuisance for uninvolved spectators, or at the most, a cause of anxiety. Of course, the purpose of most marches is to involve the spectators in some way. This might be to draw them into a positive mood, as in the Portland Rose Festival or the German Fasching parades. In the photo of double-timing demonstrators, the spectators are taking a neutral stance, while the marchers show their spirit.

Political parades may state an intention to draw in the spectators, but they may also intimidate. And from the viewpoint of adjacent businesses, taxi drivers, the transit operators, or people with personal business to attend to, a parade or a march may be seen as an attempt to assert control of the streets. The parade or march organizers feel that their festival or their cause is important enough to impose it on routine city life.

On the streets adjacent to or leading to the anti-war parade, a series of little dramas occur as previously uninvolved people find that their lives are being interfered with by the marchers.

In close-up, the anxiety on the young woman’s face might be caused by having plans disrupted, or it might be fear of entering an area in which the potential for violence between demonstrators and police lay under the surface of the peaceful march.

As if swept along by the human pressure behind it, the last Line 60 doubledecker bus running ahead of the street closures hurried through the shopping district. At this point, demonstrators reached the most fragile part of the city, confronting the end of the Saturday shopping rush and exposing the central area of West Berlin to the risk of damage in a high-profile location by breakaway groups.

Equipped with construction helmets for the lead marchers, the parade passes the KaDeWe department store. Some of the groups in the march included a cross-section of ages, rather than the young radicals of groups such as the KDP shown on previous pages. The make-up of the parade appeared designed to put groups that were willing to march peacefully in the vanguard, and the presence of children emphasized to bystanders and media observers the peaceful intent of the organizers.

Nearing the end of the march, serious faces reflect the energy committed on this day. Compare the cross-section of ages to other groups from the body of the parade, as shown on previous pages.

As the march reached the center of West Berlin, it flowed like water around the Greek temple otherwise known as the Wittenbergplatz U-Bahnhof. As a flood does, the movement of marchers was constricted by narrowed channels for its flow in the central area, and the march came to a halt.

The march was mainly directed against the United States, or at least the United States as visualized by the student Left in Germany. Among the curious bystanders watching the march were U.S. Army enlisted men whose responsibilities included protecting the right of the students to demonstrate– and the students’ right to head afterward to coffee houses and the nearest student Kniepe to talk about building Socialism. These GI’s also protected their right to ignore the opportunity to board the next eastbound S-Bahn train to a place that really needed Socialist workers, the German Democratic Republic.

Propaganda from the Left pictured the American enlisted men as “barbarians” engaged in “genocide” in Vietnam, while in Germany they said that the Western Allies were working to keep the country divided, with the result that reunification without a conversion to Socialism could only come through violence that would fill the country with mass graves.

The student Left tended to see enlisted GI’s as uneducated and politically unaware. This fit their worldview, but missed the point. The “Berlin screen” which excluded people with criminal records or behavior problems from the Berlin Brigade, combined with the high number of college graduates and mature blue collar workers drafted in the late 1960’s had brought to Berlin a diverse group who were intelligent and genuinely curious about what was going on. The student Left’s tendency toward endless ideological nitpicking and their inability to see other people outside of the frames established by their books and lectures also may account for their lack of appeal among Berlin working people. From my conversations with Berlin blue-collar workers, their view of the student demonstrators as being the sons and daughters of the privileged, willing to advance romantic notions, but unwilling to really get their hands dirty, was close to the same view held by many American soldiers.

Were these off-duty GI’s approached by any demonstrators who might have tried to agitate with them? Probably not. I walked the length of the parade with my camera, and none of the demonstrators tried to talk with me. I would walk through the Free University when it was a convenient short-cut, with no one saying anything. I wore my Dress Green uniform to the Berlin Philharmonic before I had civilian clothes, and no one said anything negative (and, in fact, I made some pleasant acquaintances). While GI’s at home in the U.S. experienced unpleasant behavior from their fellow citizens, GI’s in Berlin in this period were largely ignored by war protesters. I heard second-hand discussions of a flyer that was written for us, but the GI’s who were discussing it, all of whom had college experience at one level or another, agreed that it was written in a condescending tone by someone who thought that they would only have limited language skills.

I would like to think that many Germans who opposed the war in Vietnam were polite enough not to take it out on ordinary enlisted men. However, my brushes with the German Left and their writing lead me to the conclusion that they said nothing to us because they thought we were too stupid. While I believe that the men in Berlin Brigade were well enough disciplined to not let themselves be provoked, that was not the image that the radical Left held of us, as the following discussion shows.

On a few occasions, leaders of the radical Left did try to create a scenario in which our brutality could be demonstrated locally. In February 1968, the Berliner Vietnam Congress, which included many Germans genuinely interested in peace, found itself in a debate over a proposed demonstration/march that was aimed at McNair Barracks, where U.S. Infantry and Artillery personnel were housed. This would have created the potential for a few violent acts from within the crowd to provoke some sort of reaction from the Americans– or, also possible, from the German Labor Service guards who were on duty at U.S. facilities. Noted author Guenter Grass and Bishop Kurt Scharf intervened to successfully urge a route that would not provide this opportunity for extremists. Perhaps they were also aware of the potential consequences: at the least, loss of support for the peace movement among Berlin’s working people; at the most, always looming over 1960’s Berlin, the excuse for intervention by the numerically superior German Democratic Republic troops to restore law and order in “the special political entity of Westberlin.”

To state it more directly, a few of the romantic revolutionaries of 1968 were willing to risk starting World War III in order to advance their version of peace.

References:

Flyer, “Stoppt den US-Krieg / Frieden fuer Vietnam” from Achim Maske, 46 Dortmund, Humboldtstrasse 12 (advertising a 17 Feb 70 event in Dortmund’s Westfalenhalle II).

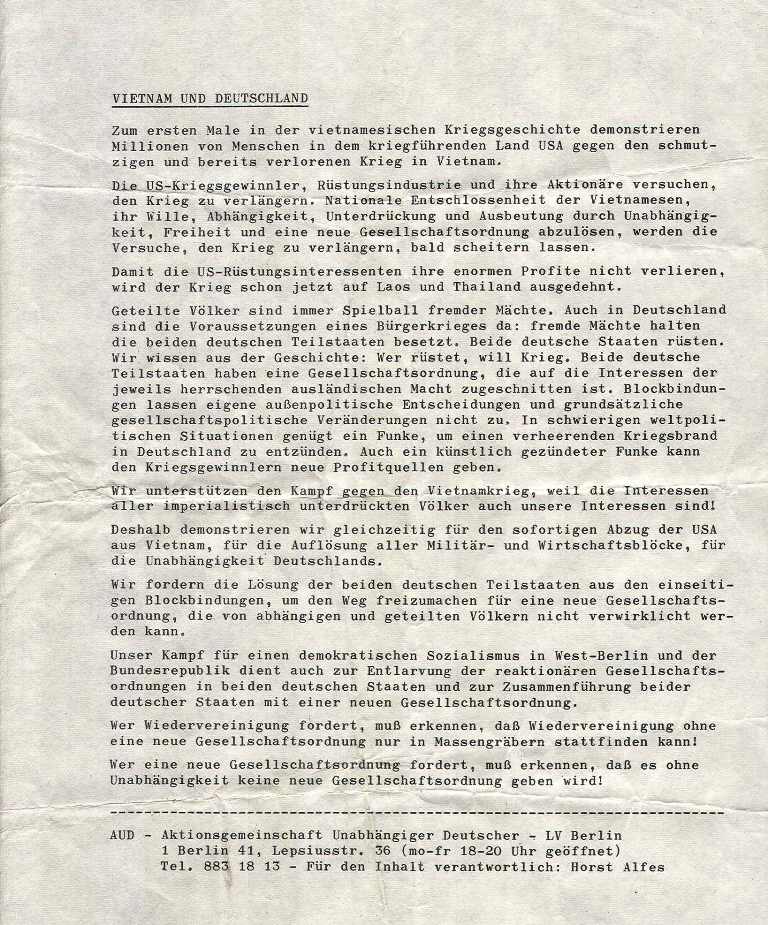

Flyer, “Vietnam und Deutschland” from Horst Alfes, AUD – Aktiongesellschaft Unabhaengiger Deutscher – LV Berlin, 1 Berlin 41, Lepsiusstrasse 36.

Gilcher-Holtey, Ingrid; Die 68er Bewegung; Verlag C. H. Beck; 2nd edition 2003. ISBN No. 3 406 47983 9; http://www.beck.de .

As the march approached its endpoint in the fading grey light typical of Berlin in November, congestion brought the middle and rear elements of the parade to a halt. While waiting, the marchers carried out parade drills.

Shoppers in the heart of West Berlin continued their Saturday errands. Police squads were lined up to protect shop windows, in case violence-seeking groups were to break loose from the cover of the peace march.

The march continued under the eyes of a crowd gathered on the Europa Center pedestrian overpass.

The panorama of a major march through the streets of Berlin attracted cameras. This film might have been used for television news in pre-videotape days. It might have been used for the last of the old-style newsreels, die Wochenschau, that still preceded feature films in Germany in 1969. Or, it could be used by an independent documentary filmmaker, hoping to capture scenes of protest… or violence.

If something sensational happened in the march, film would be rushed to Frankfurt on Pan American Airways and then transferred to a Boeing 707 to fly it to New York City to be aired the next day. Only the most extreme behavior could make the news in that situation.

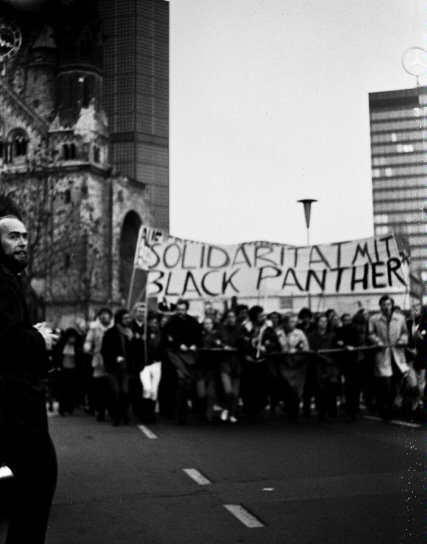

The march was an opportunity for statements of support for several Left causes. Black Panthers of the U.S. were popular with German students, who saw them as the vanguard of an expected violent overthrow of the capitalist system in the United States or at the least as persecuted reformers. Their understanding of the Black Panthers, as in the U.S. itself, reflected their own view of the world. Visual media were especially important in bypassing the often tedious writing of political groups.

Traffic, including the famous Line 19 Ku’damm Doppeldekker, waits for the parade to pass. When a parade or a march stops city traffic for whatever purpose, one of the objectives of the organizers has been achieved.

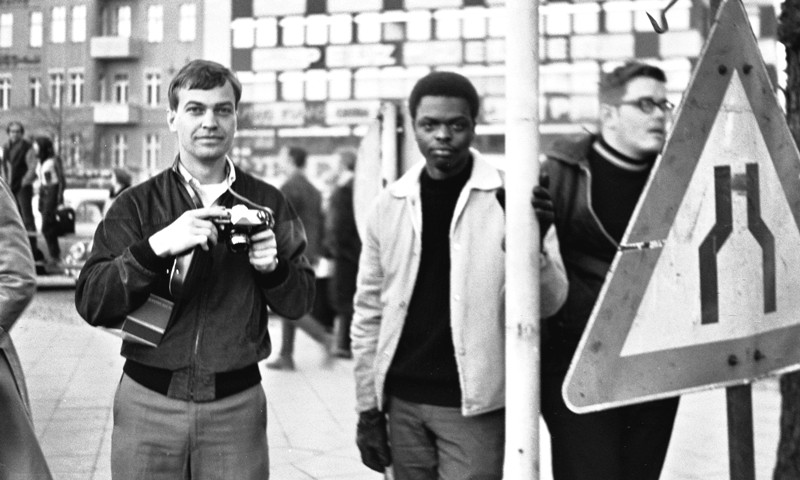

Ever since cameras moved off of tripods and into the hands of the “bourgeoisie” and the “proletariat”, no demonstration has been without someone snapping pictures. Whether to record a friend’s presence, the participation of a group that has traveled a long way to join the march, or as a record for an undercover agency of one sort or another, this march was well photographed. The photographer in this photo climbed on top of a car to get his shot.

My photographs seen in these pages were taken with a 35mm Voightlaender folding camera, built in the days when these were called “miniature” or “pocket” cameras. It was purchased “reconditioned used” for me by my father in about 1962, when he noticed my interest in photography. It had a Zeiss lens, but no telephoto lens, no light meter, and I focused it by estimating the number of meters to my subject. Without a light meter, I memorized the film data sheet and set the f-stop and shutter speed accordingly. Appropriately, it was likely manufactured in Berlin.

The film in this series was unusual for my efforts in low-light Berlin: Kodak Plus-X (ASA 160). Our conception today of how the 1960’s looked is based mainly on faster and grainier Kodak Tri-X (ASA 400). The slower film that I used here permits seeing details in the enlargements, but the wide open lens apertures to nearly the edge of the f3.5 lens, in combination with my hand-developing of the negative, account for the vaguely dreamlike effect in these scenes. I think that the reason that I used it was because I had it laying around and could not afford to buy another roll, not that I was anticipating that this might become Art.

The process of conducting and dealing with demonstrations in Berlin was much more organized than in American cities in this era. Due to the city’s history, groups that wanted to demonstrate AND the civic authorities knew what needed to be done. In this segment of a damaged photo negative, riot police may be seen guarding a pile of bricks in a building site along the parade route.

Having grown up in Oregon, I had always wondered how European rioters obtained so many bricks. What I had not realized was that their cities were made of materials ideal for heaving at the police or tossing through shop windows. Knowing this, the police put a guard detail on this construction site along the march route. The building supplies remained where they were as the march neared its peaceful conclusion.

Exhausted marchers in the enlargement above reflect the toll taken by unyielding pavement and anxiety over the possibility of violence. As individuals and small groups drifted around the parade’s terminal point, I had the feeling that the question “what’s next?” had many applications for these young people. At the least, some may have wondered where they would go from this parking lot.

The bright sun of early hours is gone and Berlin is returning to its winter grayness at the close of the Saturday march. In another two hours or so, the bright lights of the Ku’damm will sparkle in the eyes of night life seekers.

The march was also a social event; some who participated hurried away to buses or trains. Others lingered to enjoy the company of someone who they had met, or to reflect on a day that they had planned.

Print sources include:

Information Unit, United States Information Service, U.S. Mission Berlin, mimeographed daily translations of Berlin newspapers.

After this article was written additional information on the era was made available in: Lovell, Julia; Maoism: a global history; Chapter 8; Knopf; New York; 2019.

Thanks again for assistance in digitizing my damaged negatives of this event: Denver Pro Photo.

Return to first page of Demonstration, or to Troubled Times table of contents.